A no-deal Brexit – a doomsday scenario for aviation ?

7th March 2019

Firstly a declaration, I am a staunch remainer. But this article has been written using facts where available, which in some areas are hard to establish in the mist of Brexit uncertainty.

The question is how bad could a no-deal Brexit be for aviation? This article suggests that the answer could be very bad indeed with major potential negative consequences.

The bookmakers are currently giving odds of 5/1 on a no-deal Brexit, a 20% chance that this will be the outcome. As this is a possible outcome I thought it might be interesting to explore what the impact might be on the aviation sector. It is not difficult to see in a no-deal Brexit, that both sides will blaming each other for the failure to agree a deal, and that relations between the UK and the EU member states is going to be anything other than acrimonious. It is based on this premise that this article is written.

Therefore, I have deliberately taken a negative view and presenting a “worst case” scenario because it is probably worthwhile evaluation how bad it might be.

Of course the analysis is open to criticism from Brexiteers, presenting this as just another “Project Fear” point of view? But in a Debate Pack produced for the UK Parliament (Number CDP 2018-0223) published in October 2018 entitled “Effect on the aviation sector of the UK leaving the EU” it was stated that “There have also been concerns about the European Commission’s approach to negotiations on the aviation question and the relationship between the Commission and the UK Government. For example, there were reports in June 2018 that the Commission was “refusing to agree to any back-channel discussions between UK and EU aviation agencies to avert a crisis in the event of a “no-deal” outcome to Brexit”.

What we know so far

The European Union (Withdrawal) Act, which has been in place since June 2018, converts EU law as it stands today into UK domestic law. This will ensure that issues around safety and passenger rights will remain protected.

Presently it is envisaged that travel between the UK-to-EU 27 countries is expected to be visa-fee, although there is the probability that travel permits may be required. The UK has given assurances that EU passport holders can continue to use e-gates.

However UK citizens will have to pay €7 (£6.30) every three years to travel to EU countries, as a consequence of Brexit. The €7 is a fee for theETIAS (European Travel Information and Authorisation System) which is expected to come into force in 2021. The ETIAS system is Europe’s version of the United States’ ESTA.

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, the EU has proposed a temporary, one-year air services arrangement for flights from the UK to the EU from March 29th2019 until March 30th2020. Within this agreement, the European Commission has stated that it will ask UK airlines to adopt a capacity freeze which will not permit any increases in frequencies or the addition of new routes.

Olivier Jankovec, Director General of ACI Europe says that if this was approved it would “ultimately result in the loss of 93,000 new flights and nearly 20 million airport passengers across the UK-EU27 market. UK airports and their communities would be disproportionately affected.”

Quite how this can be enforced when tickets have already been sold is beyond my comprehension, and recent reports suggest that the proposal is unlikely to be enacted. What it does show is that the EU looks set to take a hard line in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

GDP impact

The linkage between GDP and the demand for air travel is well established. Leisure travel demand is driven by consumer confidence, disposable income, the cost and convenience of travel. Business travel is driven by business confidence.

Both consumer and business confidence are correlated to economic growth prospects.

Of huge significance has been the visiting friends and relatives (VFR) market. This market is directly related to social mobility and to migration trends. Increasing labour mobility, both to and from the UK has been a key driver of travel demand. In the past 10 years, 40% of the growth in visitors to the UK has come from visiting friends and relations traffic.

Demand for VFR traffic will be partly dependent on the rights that are offered to EU citizens in the UK and indeed the reciprocal working rights that are available to UK citizens in remaining EU member states.

It is not simply a matter of the new regulatory environment. The outlook for the European aviation industry will be influenced by GDP growth, which most experts expect to be negative.

European carriers will also be impacted by developments in foreign exchange rates (Sterling-Euro, Sterling-USD and Euro-USD) remembering European airlines which are structurally short the USD, the reference currency for fuel, aircraft, engines and spares. Migration patterns are also significant.

David Smith is Economics Editors of The Sunday Times. He summarises the likely economic as follows;

A no-deal Brexit would be very bad for the economy in the short-term and is the worst outcome in the long-term. Leaving a stable trading relationship with our biggest trading partner for a leap into the unknown is just about the most stupid thing a country could do. Yes, other EU countries would be hurt too – when you shoot yourself in the foot, the bullets can ricochet elsewhere – but the damage to this country would be measurably and substantially greater.

David Smith paints a picture of slower economic growth, a sharply lower pound, higher inflation, weak business investment and a loss of foreign direct investment.

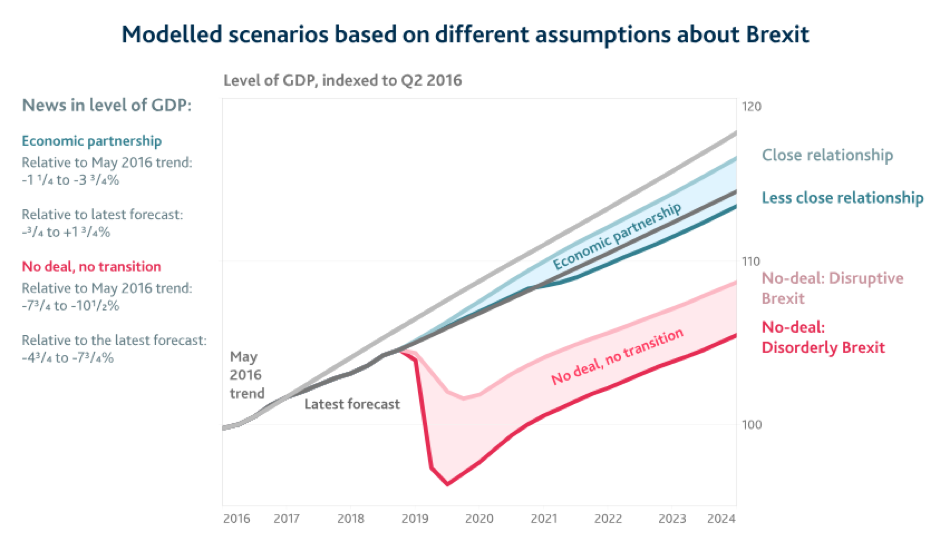

The Bank of England has presented economic scenarios based on the terms under which the UK leaves the EU and are summarised in the graph below.

Source: Bank of England, November 2018

According to the Bank of England, a no-deal Brexit would mean that GDP is between 7¾% and 10½% lower than the May 2016 trend by end2023. Relative to the November 2018 Inflation Report projection, GDP is between 4¾% and 7¾% lower by end-2023. This is accompanied by a rise in unemployment to between 5¾% and 7½%. Inflation in these scenarios then rises to between 4¼% and 6½%.

The key points outlined by the Bank of England in no-deal scenario are that:

- GDP drops 8%

- Sterling falls 25% to below parity with the dollar

- House prices fall 30%

- Commercial property prices plunge 48%

- Unemployment rises to 7.5%

- Inflation accelerates to 6.5%

- BOE benchmark rate rises to 5.5% and averages 4% over 3 years

- Britain goes from net migration to net outflows of people

It is difficult to see anything other than a highly negative impact on the demand for air travel. That is just the impact of macro-economics. In 2009, UK GDP fell by 4% and UK airport passengers fell by 7%. Given the GDP/traffic multiplier that is fundamental to the airline industry an 8% fall in GDP could see a drop in passenger numbers of potentially 12-16%.

Let’s consider a few other aviation specific factors.

Regulation

Airlines, airports and other industry stakeholders have hoped that the UK might remain in the EU Single Aviation market, the multi-national aviation area which fully liberal traffic rights. As MAG Group CEO Charlie Cornish has said, “The best result for the aviation industry would a deal which preserves the liberal flying freedoms and competitive approach to the aviation market that have driven connectivity and economic growth across the continent over the last couple of decades.”

The UK in a Changing Europe stated in a September 2018 paper that:

Brexit in any form will be disruptive for airlines, but failure by the UK and the EU to reach agreement would leave the industry in chaos. Because the sector has its own system of regulation, based on the 1944 Chicago Convention, there is no WTO safety net in aviation. Moreover, although the Chicago system has provided a stable framework for the development of aviation since the second world war, it is unwieldy, difficult to change and restrictive.

Some argue that … fears are exaggerated and that it is in the economic interests of both the UK and the EU to avoid [no-deal]. It is true that contingency measures could be mobilized to retain basic connectivity – for example, the UK could grant access unilaterally – but such steps would merely limit the damage. They would certainly not provide for a continuation of the advanced system that currently exists. A UK-EU air services agreement, as well as UK bilaterals with third countries, would take years to negotiate, as each side aims to secure the best deal for its airlines under uncertain conditions.

The UK is the largest single market for short haul air transport accounting for some 13% of short haul departures in Europe.

A no-deal Brexit creates a significant risk that aviation regulatory structures governing UK air transport could mean that the UK falls back to historical regulatory structures. Before the EU Single Market, to have a UK airline licence, for example, it was necessary to be majority owned and controlled by UK nationals.

UK airlines would need to demonstrate majority UK national ownership and control, as would EU airlines would also need to demonstrate majority EU ownership and control, excluding UK investors.

A reversion to old bilateral agreements will be interesting. The UK has mitigated the risk in arguably the most important and profitable market outside of the EU by signing an Open Skies agreement with the US in November 2018 that that will maintain air links between the countries after the UK leaves the EU. The UK-US market is the largest across the Atlantic, with some 10 million annual passengers representing 29% of all traffic between the USA and Europe in 2017 according to the US Department of Transportation.

It would appear that Norwegian, owned and controlled from Norway, will be treated as having historic rights and will be allowed to continue to fly from the UK to the US. But new entrants from the European Union and related countries hoping to cash in on the richest aviation market in the world would not be granted flying rights.

The outcome of the UK leaving without a deal makes, in my opinion, the probability of the UK falling out of the EU single aviation area without a negotiated bilateral much higher, and therefore open up the reversion to old style regulation would mean that traffic rights could revert and shrink to national airlines of the two countries in each market.

The UK has long had bilateral agreements with many of its important markets, such as the US, which were superseded by EU-third party agreements. The ITC has said that as a result of EU membership UK airlines benefit from 42 Air Services Agreements entered into by the EU with countries inside and outside the EU including the US and China.

Once it has left the EU, the UK will need to have negotiated new agreements with those countries or to have negotiated with the EU and those countries to continue as a party to the agreements as a non-Member State.

In the event of the EU and the UK failing to reach any bilateral agreement, it would appear that the regulatory structure might fall back to the legacy bilateral agreements in place before the establishment of the single market. As the UK had traditionally taken a supportive stance on airline competition many of the bilateral agreements were very liberal.

Whilst I believe that flying will continue after the temporary arrangements end, the continuity thereafter is subject to massive uncertainty, with pan-European operators like Ryanair and Wizz being restricted to services to their home markets of Ireland and Hungary from the UK.

The UK has signed nine other Open Skies agreements. Five of these are to significant aviation markets; Canada, Switzerland, Israel, Morocco and Iceland. The other four are much smaller aviation markets in Central and Eastern Europe; Albania, Georgia, Kosovo and Montenegro.

Brexit campaigners often quoted that the Commonwealth countries represented a major opportunity for the UK in terms of closer economic ties but the UK is yet to conclude a an Open Skies agreement with either Australia or New Zealand. The UK’s existing bilateral with Australia specifically permits the UK to designate carriers from any EU country, which the Australians may want to change in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

The EU has in place or is in negotiation with over 60 countries or regional trade associations regarding aviation agreements, either a “horizontal” or “comprehensive” agreements.

Ownership and control

The EU single market of course relaxed the rules on airline ownership and control within the EU aviation area, and thus paved the way for the creation of Air France-KLM, IAG and the multi-national Lufthansa group and the pan-European operations of Ryanair, easyJet and Wizz. The UK’s stance seems to be that if an airline has a UK Air Operators Certificate (AOC) this allows the airline to function as a UK airline, with no reference to the nationality of the shareholders. Whether the third parties that the UK has to negotiate with, the EU and other countries elsewhere, will accept this must be in considerable doubt.

easyJet was the first mover in establishing an EU AOC alongside its existing UK and Swiss AOCs. With the dual EU and UK nationality of its founder, Stelios Haji-Ioannou leaves easyJet better placed to face potential regulatory issues over ownership and control.

The ownership structures of IAG’s EU airlines, as well as Wizz, and Ryanair would be in question. These Pan European businesses would defend traffic rights by demerging into UK and EU businesses. Yet, with a less stable regulatory regime, the risks of establishing UK businesses would be greater for the Pan European businesses. In this situation there may be greater need to demonstrate genuine UK ownership and control of UK.

The ownership regulations leaves IAG facing structural challenges that could require the demerger of BA from the EU operating companies. IAG has been reluctant to publically disclose its national ownership structure, but it is thought that IAG would likely fall below majority EU ownership requirements.

IAG also faces issues regarding traffic rights such as the Belfast based flying of Aer Lingus and the UK-Italy operated by Vueling.

As Andrew Lobbenberg, the airline analyst at HSBC Banks says;-

“We see IAG particularly vulnerable in the context of ownership and control given that post Brexit it would not be owned or controlled by EU nationals. We consider the company’s focus on the domicile of the Holding company and the scale of its businesses as an irrelevant appeal to realpolitik. Moreover, we see the Iberia and BA trust structures as irrelevant in the context of meeting the requirement for majority EU ownership and control. We see IAG’s best contingency plan lying in Qatar Airways somehow re-domiciling its 20% stake into the EU, but this would be complex.”

For Ryanair and Wizz they face the possibility of needing to establish independently owned UK businesses, to defend traffic rights to countries other than their home countries.

In a no-deal scenario I foresee complex ownership and control challenges for airlines including Ryanair, Wizz and IAG. Air France-KLM’s investment into Virgin Atlantic could also be untenable. It is perhaps Lufthansa, among the European majors that has least regulatory risk regarding Brexit.

Legal challenges could be mounted by regulators or perhaps by airlines that want to disrupt the operations of their competition.in several of our considered scenarios.

On both a Europe wide basis, as well as to and from the UK, the overwhelming majority of services of both Ryanair and Wizz are dependent on the liberal seventh freedom traffic rights of the single market. For example, should operations fall back to the historical bilateral environment, Wizz, as a Hungarian airline would have been able to fly exclusively to and from Hungary. In 2017, 88% of Wizz’s services to and from the UK would not be permitted.

Safety

Currently the UK benefits from being a member of the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) which covers safety issues across all Member States. A no-deal Brexit puts the UK’s membership in doubt.

In a March 2018 report the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Select Committee set out the potential consequences of a UK exit from EASA:

If the UK is to make a managed departure from EASA, it would require a transition period in which special arrangements are made with the EASA, the US Federal Aviation Authority and other global regulators. The Civil Aviation Authority would need to undergo a major investment and recruitment programme if it is to take over the functions of EASA at some point in the future, and Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreements with mutual recognition agreements would need to be negotiated with the EU, US and other major markets. Given the complexities involved, this transition may need to last beyond the two years that the Prime Minister has said is likely to be appropriate for the economy-wide implementation period. This disruptive and costly process is unlikely to result in any significant divergence in regulation.

Conclusion

A no-deal Brexit would appear to be a potential calamity for the aviation industry. The demand for air travel will be adversely affected by a major contraction of the UK economy and the risk of contagion on the economies of the remaining EU member states. Leisure travel seems most at risk being impacted by a fall in the value of Sterling, lower disposable incomes, higher levels of unemployment, falling house prices etc.. Softer issues will also have a negative impact, consumer group Which are predicting five hour queues at immigration at Spanish airports such as Alicante and Tenerife, higher data roaming charges, more complicated and costly procedures for car hire etc..

And then there are also the issues around the future regulatory structures around Air Service Agreements and bilaterals and the complexities of ownership and control. The title I chose for this article uses the word “Doomsday” whose definition is, according to the Macmillan dictionary, “an extremely serious or dangerous situation that could end in death or destruction”. Perhaps using the word “Doomsday” is a little strong…………………but then again perhaps not.

Author: Tim Coombs